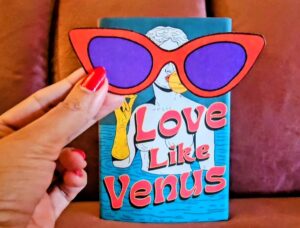

If you’re attending BookCon in NYC this April, I have a preorders up at Beventi, the platform that connects book lovers with authors. Preorders for pick up at Javits Indie Alley on Beventi for To Love Like Venus come with customized bookmark sunglasses. Because you’re BookCon fabulous.

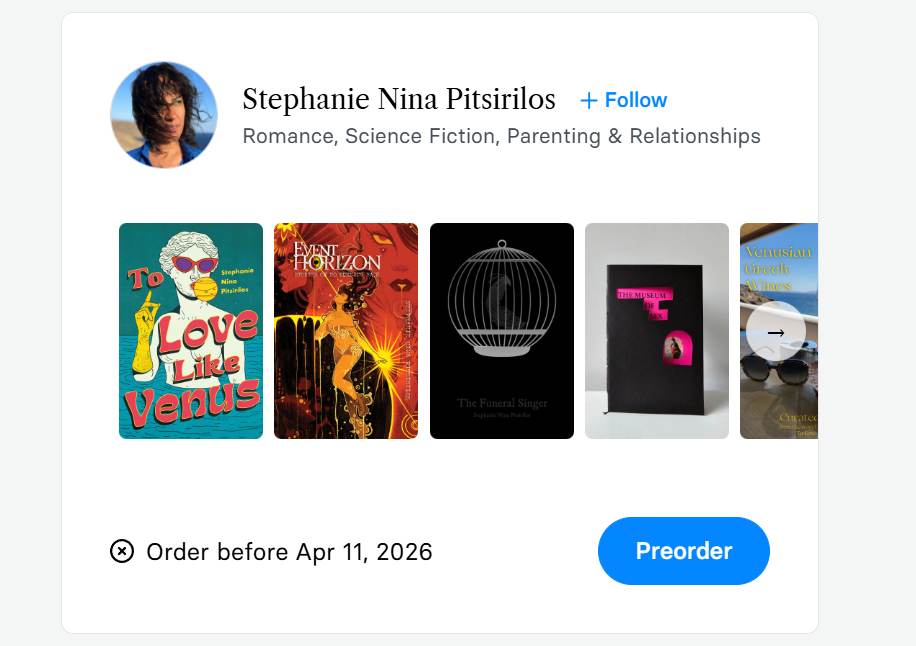

You’ll also find a discounted Venusian Bundle that includes the genre-blending, multi-medium universe of themes of love, desire and lines crossed that is: To Love Like Venus, The Museum of Sex chapbook, Venusian Greek Wines chapbook, and a discounted Event Horizon: Stories of No Turning Back, plus a free character sticker.

You’ll also find a discounted Venusian Bundle that includes the genre-blending, multi-medium universe of themes of love, desire and lines crossed that is: To Love Like Venus, The Museum of Sex chapbook, Venusian Greek Wines chapbook, and a discounted Event Horizon: Stories of No Turning Back, plus a free character sticker.

Why preorder via Beventi: It gauruntees a signed book is waiting for you at the show, especially for limited runs of special prints like my handmade chapbooks. Plus you get those cool sunglasses. Order by April 12th.

Link to my Beventi Preorder at BookCon page: https://beventi.co/orderform/xj0xau6ztg

There’s no category on there for literary fiction, so my other genres are represented.

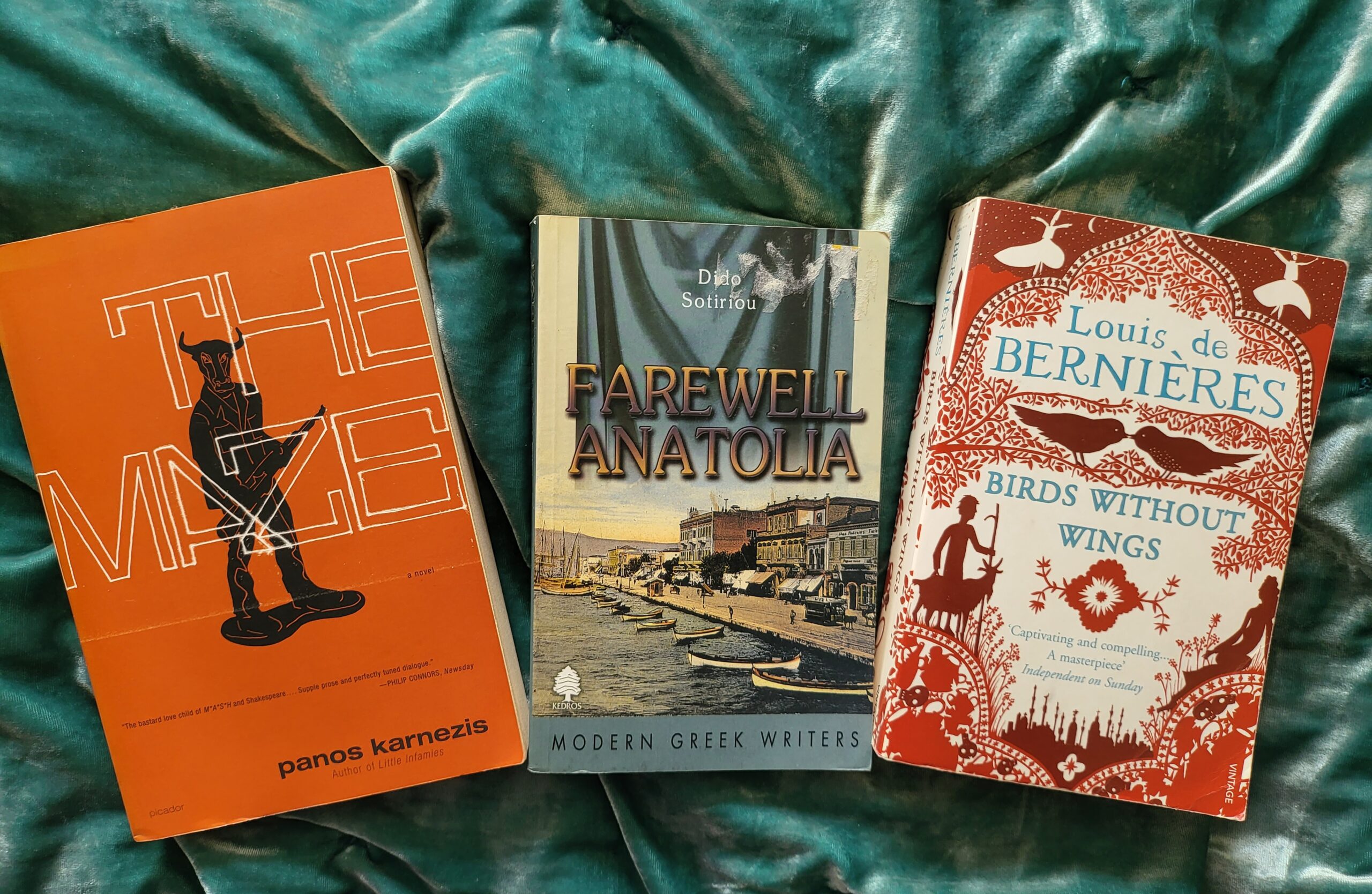

Some exquisite novels written about Anatolia and The Great Catastrophe

Some exquisite novels written about Anatolia and The Great Catastrophe